[By Rob Roehm. Originally posted December 31, 2011, at the now defunct REH Two-Gun Raconteur Blog.]

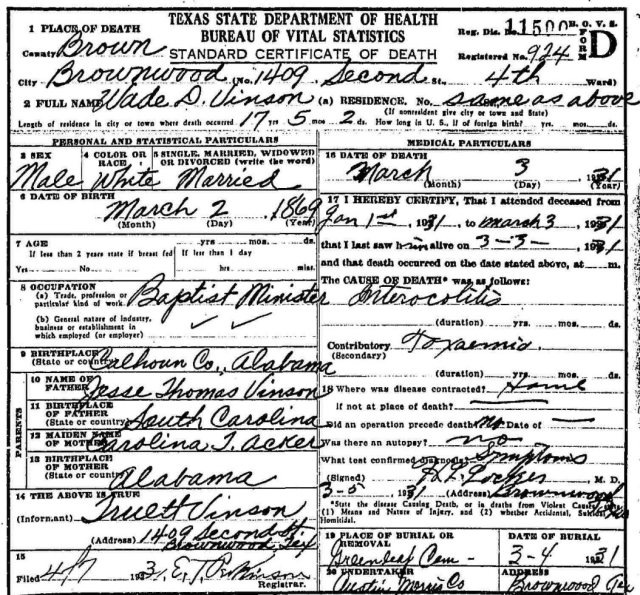

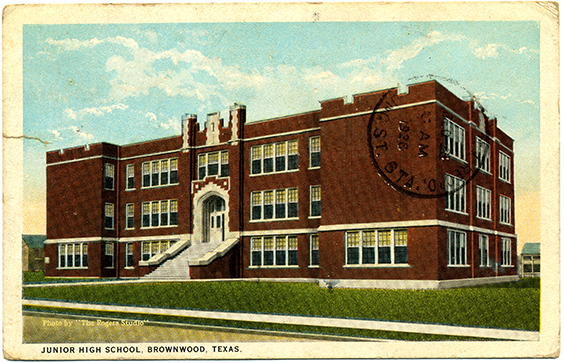

In his January 7, 1925 letter, Robert E. Howard tells Clyde Smith that “Another one of my friends got married. He and the girl he married graduated from this school with me. We were all classmates together” (Collected Letters, vol. 1, p. 41. REHF Press). I’ve often wondered who the pair was, and now, with a little help from Linda Burns at the Cross Plains Public Library, I don’t have to wonder any more.

As reported in the Cross Plains Review for both May 5 and 19, 1922, there were only ten graduates from Cross Plains High School in 1922: Ruth Brewer, Clara DeBusk, Willie Swan, Irene Jones, Winnie Swan, Winfred Brigner, Robert Howard, Louie Langley, C. S. Boyles, Jr., and Edith Odom. We know it wasn’t Robert Howard who got married, and I have already eliminated Edith Odom as the bride; that left only eight possibilities. Because their last names don’t change with marriage, I focused on the boys. Other than REH, there were only four; how hard could it be?

Louie Langley (1904-1955), who became a Dallas attorney, married Ruby F. Brentlinger, not a CPHS grad: down to three.

Turns out Willie Swan was a girl, Winnie’s twin: down to two.

For a while I thought that it might be C. S. Boyles, but after reading an article in the May 8, 1925 Yellow Jacket (reprinted in School Days in the Post Oaks), I found that he had married one Ilene Embry on July 2, 1924. She was not a graduate of CPHS in 1922, so I marked Boyles off the list, too. Only one candidate remained.

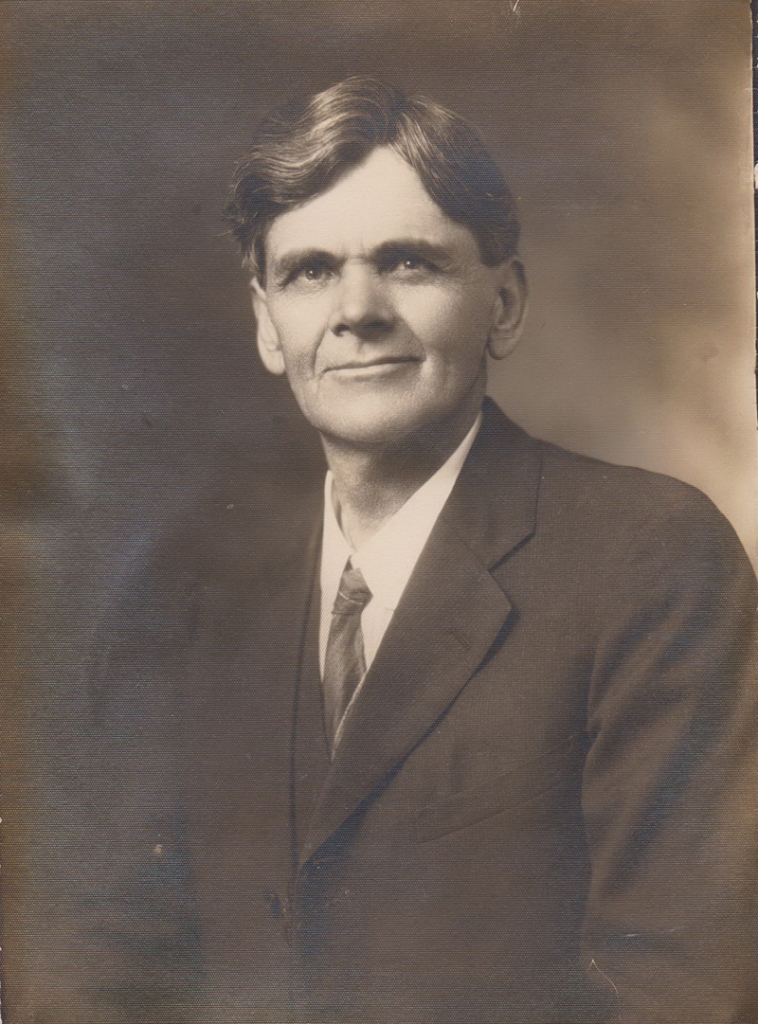

Besides Boyles, the only other graduate I’d heard of before was Winfred Brigner (whose name is sometimes misspelled as Winifred)—one of the REH photos owned by Project Pride (above) has Winfred’s name written on the back—so, having eliminated the other guys, I focused my attention on him.

Brigner appears in Howard’s semi-autobiographical novel, Post Oaks and Sand Roughs, as “Fred Gringer.” In the novel, Howard’s alter-ego, Steve, says that Gringer is one of only two “Lost Plains” residents “whom he really considered as friends.” He goes on to say that Gringer “was married and teaching school now in a small village north of Lost Plains and Steve seldom saw him.” This would have been in 1925. Later on, he adds the following:

He saw Fred Gringer occasionally now, as the youth’s school was out and he sometimes came into Steve’s office to argue religion. He was somewhat older than Costigan, a tall, powerfully built Northerner who had drifted into Lost Plains with his family some years before, following the track of the oil booms. He was a lonely sort of dreamer, a little like Steve, though with much different ideas on most subjects. He was strictly religious and with him Steve always drifted to the other extreme, realizing that Fred considered him a rank infidel and in eminent danger of everlasting torment. Steve usually wore a mask of callous buffoonery around Gringer, and many were the black moods out of which he jested the Northern youth.

Steve, contrary to his usual custom, showed the incomplete manuscript of “The Isle of the Eons” to Fred and asked him to read it. He did not ask for criticism for Steve considered that he was the best critic of his own work. After reading it Fred said:

“This is pretty good, but I think there are some mistakes in English – I noticed several.”

Steve was irritated though he tried not to show it.

“The English dont matter so much,” said he, “I’ll correct that. The idea is to get it over. The main thing in writing is to say what you want to say, in an interesting manner. Of course my English is far from perfect but that will improve by practice. As for these mistakes, I’ll correct them.”

Toward the end, we get a bit more:

Fred Gringer was cooking in a cafe for his living. His wife had divorced him, his teacher’s certificate had run out, and he was drifting with the tide, longing to go to college and get a permanent certificate, to teach in some large school and work his way up to the position of coach. But he could see no way for his ambitions to be realized.

In “Steve’s” final rant, 1928 in the real world, we learn even more:

“And there’s Fred Gringer. Finished high school at Lost Plains same year I did. His old man had been beat out of his year’s work by a slick crook he’d been drillin’ for and they couldn’t send Fred to school. He was plannin’ to finish high school in Redwood with me—you know till just lately Lost Plains didn’t have an affiliated school and you couldn’t get into a college on the strength of graduatin’ there. Had to have one more year at least, somewhere’s else.

“So Fred started teachin’ in little country schools. He had hell because he was a dreamer too. But he stayed with it, fought it out and had some money saved up to go to college on when he suddenly decided that the idea was the hokum and got married. Then he couldn’t go to school of course, and had to keep on teachin’ in little crumby country schools and they ain’t nothin’ will kill a bird’s guts quicker.

“Him and his wife couldn’t get along and finally she divorced him. He kept on sluggin’ but his certificate run out and he felt so plumb beaten that he didn’t take the trouble to take the examinations again.

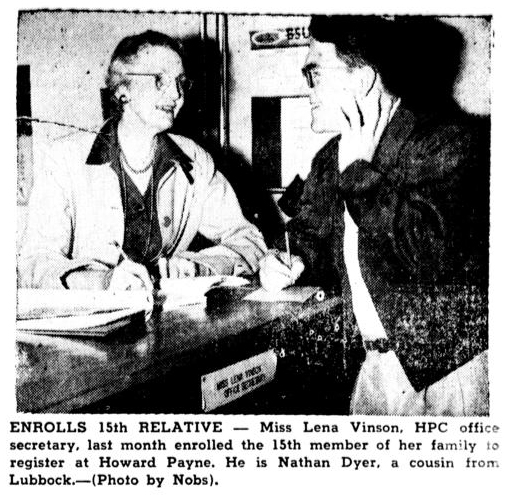

“He cooked in cafes and the like and just drifted along like the rest of us till right lately. Now he’s in the smallest and crumbiest college in the state, takin’ seven subjects to get through in a hurry, doin’ janitor work to pay his board and tuition, and comin’ out for all athletics.

“He wants to be a coach and to work up to that position he’s got to start in a larger school than those he’s been teachin’ in. And to get a larger school he’s got to have four years of college work which will give him a permanent certificate.

“I got no kick at that rulin’ specially. I’ve had some samples of ignorant country school teachers. I say, make ’em be half way educated anyhow, but give ’em a chance to get that education. And Fred never got no breaks when he wanted to go to school. He wrote to a flock of colleges but not a peep outa any of them. Why? Because he didn’t have any dough. He cooked himself with ’em when he told ’em that he didn’t have any money and wanted to work his way through school. He wrote Gower-Penn [Howard Payne] that, and they didn’t even answer his letter. The one unpardonable sin in America is bein’ without dough. Joe Franey, who’s coachin’ there now, didn’t even think enough of him as a prospect for the college to send Fred any literature about it. Damn him! He’s just like all the other college scuts—a cursed boot-lapper at the feet of the wealthy. They don’t want men with ambition and guts—they want liquor swillin’, flapper pettin’, yellow-spined cake eaters that’s spendin’ the old man’s dough free and easy, God damn their souls to Hell.

“Then I personally saw the coach of Moses-Harper [Daniel Baker] and he came and talked with Fred and promised a lot—and come back to Redwood and did not one damned thing. Fred had to go to a college so small that they was willin’ to give a man a break. Fred ain’t lookin’ for no cinch—he ain’t wantin’ to get by on his face. All he wanted and all he asked for was the promise of a job by which he could work and pay his board and tuition. And the bastards wouldn’t even give him a hand. Oh, no, they wanted wealthy sons-of-whores.

“They don’t know what they passed up. Fred’s an athlete and some day, if he gets any breaks at all, he’ll be a great coach. He’s a runner, too. He’s broke the world record on the hundred yard dash, unofficially, of course. But they passed him up for some flat-chested bastard who couldn’t carry a football through a line of drunken flappers or for some scut who’ll put in a year at the game—spend two minutes in a scrimmage and the rest of the time struttin’ around over the field for the damfool girls to admire.”

Howard’s hyperbole aside, most of the information I’ve found on Brigner seems to match up with his Post Oaks counterpart.

The 1910 Census has Winfred in Cedar Township, Wilson Co., Kansas, with his father Charles W. (a driller in the gas wells), mother Bell, and younger brother Charles Leroy. Sometime before the 1920 Census was enumerated, the Brigners moved to Callahan County—Cross Plains, to be exact—where his father worked in the Oil business.

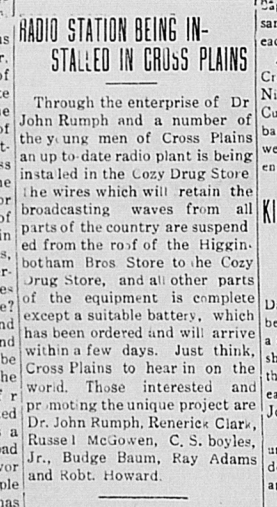

Following his son’s 1922 graduation, Charles appears to have been one of the main investors in at least one venture, as this notice from the August 17, 1923 Mexia Daily News suggests:

NEW WILDCAT STARTED NEAR CROSS PLAINS

CROSS PLAINS, Callahan Co., Texas, Aug. 17— Machinery has been unloaded for a new wildcat test to be drilled for Brigner & Jose on the Odom ranch, eight miles west of Cross Plains. The new well will be located a short distance north of the old Odom test of the West Texas Oil and Gas Co, which was abandoned about two years ago. Special effort will be made to develop a shallow pay found in the old well at a little below 600 feet, and which was claimed showed for 20 to 25 barrels of production.

The above article caused me to investigate Edith Odom, but as my previous post shows, she never married Winfred.

The next item on Winfred comes, again, from the Cross Plains Review. It ran a little item in its September 18, 1925 edition: “Winfred Brigner will teach at Cado Peak school, this term.” This would be the “small village north of Lost Plains” mentioned in Post Oaks. The 1930 Census lists him as a laborer doing “odd jobs” and living at home with his parents, without a spouse. I seem to remember finding an article that mentioned Winfred as having run for a public office in Cross Plains during the 1930s. I can’t locate that article just now, but I recall that he was soundly defeated. Also in the 1930s, brother Charles Leroy had a little trouble with the law:

Man Wanted In Callahan County Captured Here

Charles LeRoy Brigner, wanted by Callahan county officers, was captured here Saturday by Deputies Andrew Merrick and Bob Wolf. Brigner faces two felony indictments in Baird, according to officers. (Big Spring Daily Herald, Nov. 25, 1934)

After serving as a pallbearer at Robert E. Howard’s funeral in 1936, Winfred drops out of sight for the most part. Army Enlistment records show a Winfred N. Brigner of Callahan County enlisting at Abilene on August 27, 1942 for “the duration of the War or other emergency, plus six months.” He had one year of college and was divorced “without dependents.” Brigner died February 2, 1954 and is buried in the Cross Plains cemetery.

Having run out of sources on my end, I gave the Cross Plains Public Library a call. They have a Genealogy section; maybe, I thought, someone there could help me.

A few days later, I called back to see if they’d found anything. None other than Ann Beeler, author of Footsteps of Approaching Thousands, had done some digging and found that Brigner had married his CPHS classmate Winnie Swan on December 24, 1924—just two weeks before Howard wrote to Smith—and that he was divorced sometime before 1930. Brigner, it seems, never remarried; Winnie died in 1984 with the last name of Breeding.