[By Rob Roehm; originally published in Onion Tops #83, REHupa mailing 286, Dec. 2020. This version updated and lightly edited.]

When the uncle for whom I was named—a prominent banker on the coast—was mixed up in the “round bale war,” he hired a private detective to guard his house and protect his family when he himself had to be absent, but he asked no man to protect him.

—Robert Ervin Howard to H. P. Lovecraft, ca. September 1932

After the Civil War, George W. Ervin (b. 1830), left Mississippi and headed west to Texas with his wife, Sarah Jane (1832), and seven children: Marilda C. (1850), Christena C. (1852), Christopher C. (1855), John P. (1856), William V. (1860), Georgia Alice (1862), and David D. (1865). Quickly settling in Hill County, Robert Thomas Ervin was born there on January 30, 1867. His brother John would die there the following year. In documents, Robert E. Howard’s namesake appears most often as “R. T. Ervin,” though sometimes the middle initial is wrong, and/or the last name is misspelled as Erwin, Irvin, Ervine and other guesses or mistakes. (Dark Valley Destiny has “Robert F. Ervin,” a likely transcription error.) I’ve retained these errors in my transcriptions throughout this article.

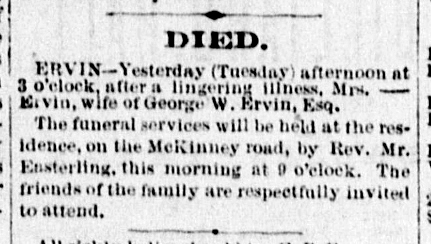

By the time of the 1870 Census, George Ervin had amassed more land in Hill County than most of his neighbors. Selling much of it, the family (which now included one Hester Jane, born that June) appears to have spent a little time early in 1872 in Shady Grove, Arkansas, before settling back in Texas. Operating as a real estate agent in Dallas by 1874, Ervin’s fortunes rose with his January 5 election to the Board of Directors of the Dallas & Wichita Railroad and his selling of parcels of property in a section of land called “Ervin’s Addition.” That year brought Ervin’s last child with Sarah Jane, Lizzie, but 1874 would also take its toll: Sarah and Lizzie both died in June, and nine-year-old David died in October.

On April 14, 1875, eight-year-old Robert Ervin got a step-mother, Alice Wynne, and not long after, a new home in Lewisville, in Denton County, as well as a new sister, Coralie (1876). While waiting for the railroad to arrive in town, George Ervin continued selling lots in Ervin’s Addition, ran a hotel in Lewisville, and invested in mineral rights—the family was quite comfortable. Other children were born: Jessie in 1880 and Annie in 1882. It is here in Lewisville, one supposes, that Robert Ervin first attended school and watched his older siblings move out and establish themselves. By the end of 1885, only three of the children born to Sarah Jane were still in the household: daughters Georgia Alice and Hester Jane, and son Robert Thomas. With his finances in very good shape, George Ervin decided to move the family to a more sophisticated community.

Before the rise of Mineral Wells, Lampasas was a hot spot for the well-to-do in Texas. “In 1882 the Gulf, Colorado and Santa Fe Railway was extended to Lampasas, ending the town’s cattle-trailing and gun-fighting era. As the western terminus of the line, Lampasas became a trading center for West Texas. New business houses were established, real estate prices rose, and the population soared to an estimated 3,500” (Handbook of Texas Online). When the Ervins arrived, late in 1885, the boomtown had moved on, but the town had other attractions: “By 1882 tourists discovered the mineral springs and Lampasas became a health resort. In that year a syndicate of railroad officials built the Park Hotel near Hancock Springs and ran a mule-drawn streetcar to the railroad station. Subsequently, the Hannah Springs Company built the Hannah Bath and Opera House, where the Democratic state convention was held in 1893” (Handbook of Texas Online). On January 9, 1886, G. W. Ervin dropped $1,500 (the equivalent of $40,000 today) for three lots in the “Lampasas Springs Company’s first addition to the town of Lampasas.” This was the first of many such transactions.

It is unknown what type of schooling or training Robert Ervin received before arriving in Lampasas at the age of nineteen, but it seems he must have been good at math. The December 1, 1888, Lampasas Leader reported that “R. T. Ervin has accepted a position as note clerk in the Galbraith Bank, taking the place of Geo. W. Rodgers, resigned.” The Galbraith Bank was in downtown Lampasas. R. T. Ervin had found his calling.

The next summer, in July 1889, Robert Ervin appears in several society articles, attending parties with the Lampasas elite—which sometimes included his sisters, Alice and Hester. On July 20, the Lampasas Leader ran a list of young men who were “organizing a military company”—R. T. Ervin was on that list. And while he earned advancement to assistant cashier at the bank, he wouldn’t remain in Lampasas for long; later that year he accepted a position as cashier at the First National Bank in Beeville, or possibly Bellville, Texas, closer to the Gulf (newspapers have conflicting reports, though Bellville makes more sense to me). The following year, 1890, George Ervin liquidated his holdings in Lampasas and moved the family to Exeter, Missouri. Robert Ervin was on his own.

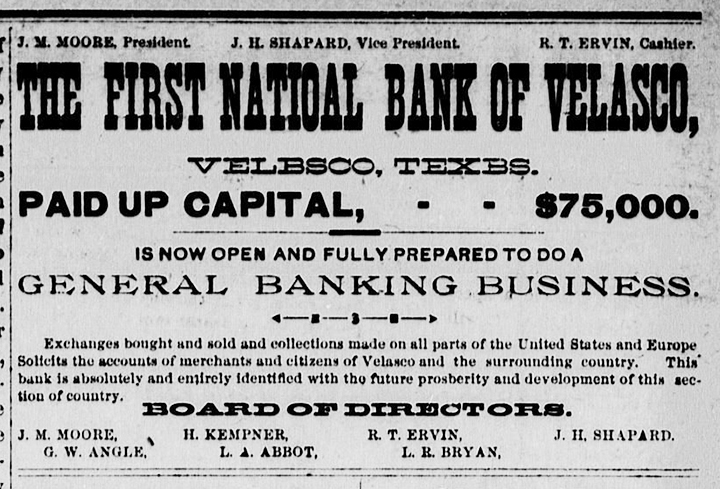

On April 30, 1891, he “was at the Capitol,” according to the Galveston Daily News, and in July, he moved again. On July 23, 1891, the Galveston Daily News reported that “R. T. Ervin, cashier” had resigned from his post at the First National Bank at “Beeville.” His resignation must have been due to an opportunity to the east, in the newly established town of Velasco: “The new town of Velasco was surveyed and laid out in 1891, when a new Velasco post office was established. The port was officially opened by the United States secretary of the treasury on July 7, 1891” (Handbook of Texas Online). As early as September 19, 1891, Ervin is acquiring land in Brazoria County and, by November 14, 1891, the Velasco Times was mentioning him as one of the directors of the Velasco Commercial Club, running ads featuring “R. T. Ervin, Cashier,” and listing him as one of the Board of Directors of a new endeavor:

First National Bank of Velasco

The organization of the First National Bank of Velasco with a capital of $75,000 was completed on the 12th and the bank will open as such, December 1st, prox.

The directors are Messrs J. M. Moore late president of the First National Bank of Lampasas, R. T. Irvin late assistant cashier of same bank and late cashier of the First National Bank of Bellville, George W. Angle, of the Brazos River Channel and Dock Company, Texas Land and Immigration company etc. J. H. Shappard, of Shappard Stevens & Co., all wealthy men of this state with headquarters at Velasco, L. A. Abbot, of Abbot & Marmion, one of the city’s most financially solid firms, Louis R. Bryan, a well known lawyer and owner of much valuable unencumbered real estate in this and adjoining counties, and H. Kempner banker and merchant of Galveston and one of the richest men in that very rich city.

Officers elected were J. M. Moore, president; J. H. Shappard, vice-president, and R. L. Irvin, cashier.

From the above it will be seen that this is probably the strongest bank in the State if not in the whole Southwest. The aggregate wealth of the above mentioned gentlemen, in clear real estate alone, that is constantly rising in value, runs far up into the millions, and each one of them is known to be a first class thoroughly trained self made business man in every respect. Messrs J. M. Moore and R. L. Irvin are well and favorably known in financial circles all over the South and West and in the great money centers of the East. Of Mr. Moore, the Lampasas Leader, his home paper says editorially:

“Mr. Moore is one of our most substantial citizens, and is an exceedingly safe and conservative financier, with none of the elements of the miser in his make-up. [. . .]”

Once established in his new position, Ervin resumed the society life. “A Christmas Treat,” in the December 27, 1891 Velasco Daily Times, describes the celebration of the town’s first Christmas in sumptuous detail. The Hotel Velasco was “gaily decorated” for the assembled men. The bill of fare included oysters on the half shell, turtle soup, turkey with oyster sauce, saddle of venison, absinthe et cognac, and many other delicacies. Later, “Responding to toasts, short, pithy and appropriate speeches were made,” including “To Velasco’s financial prosperity,” delivered by Ervin. After the speeches, “the party then adjourned to enjoy their fifty cent Havanas in Mr. Crowe’s department of the hotel where they passed the evening in that serene and happy state of mind so frequently mentioned in scripture.”

The February 10, 1892 Velasco Daily Times has this:

One of the most intricate and artistic pieces of carving from a photograph was viewed last night by a TIMES reporter at the Palace of Beauty. It was a two dollar and fifty cent gold piece engraved, with an excellent photograph of R. T. Ervin, cashier of the Velasco National bank, and was executed by E. G. Schoeler. It is a splendid piece of work and well worth viewing.

In its “Political News” column for March 7, 1892, under “Velasco Politics” the Fort Worth Gazette describes a meeting of “planters, stockmen, sea coast captains, railroaders, laborers, merchants and professional men,” including Ervin. They are “all well-known citizens and property holders, are a committee to take future action in bringing Democracy to the front in Brazoria county under the motto, ‘Turn Texas Loose.’”

Ervin’s star was rising in the growing community and his popularity increased. The March 11, 1892 Velasco Daily Times described the Velasco National Bank as “one of the solid business institutions of Velasco of which she is proud. It began business here December 15th, and has been doing a large and increasing business ever since.” The same article describes Ervin and the other officials as “very popular among our business men.” There were plans to “erect a handsome two-story brick building [. . .] of pressed brick, with iron front trimmed with cut stone and plate glass doors.” The March 20, 1892 Velasco Daily Times reported, “R. T. Ervin, the popular cashier of the Velasco National bank, left yesterday for a short visit to Houston.” This was the first of several visits to the big city.

And banking wasn’t his only interest. Several court documents available online indicate that Ervin had a side gig dealing in real estate—like father, like son. The few records available indicate that he made more than $600 in land deals near Velasco in less than two years. That’d be around $20,000 in 2023 dollars. And he was just getting started.

With the Velasco bank booming, and his land speculation bringing in the coin, Ervin set his sights on the next opportunity, as reported in the January 25, 1893, edition of the Galveston Daily News under “Texas Banks”: “R. T. Ervin of Velasco and associates have applied for authority to establish the First national bank of Wharton.” This was also reported in The Banker’s Magazine and Statistical Register for February 1893. The March 7, 1893, Galveston Daily News had more details from Wharton: “Mr. R. T. Ervin of Velasco is in town making arrangements to establish a national bank at this place. The building which he will occupy is in course of construction and will be completed about the 1st of April. Immediately thereupon he will move in and begin business.”

On March 17, 1893, the Velasco Times bid farewell to one of its rising stars: “R. T. Ervin, ex-cashier of the Velasco National Bank, and who has organized a bank in Wharton, paid his Velasco friends a short visit this week and departed Wednesday for his new home. We wish him success.” Ervin was just 26, a successful business man with contacts in the financial world and a growing influence in his chosen sphere—things couldn’t get much better.

Erwin-Clarke.

Last night Trinity church was crowded to its utmost capacity to witness the wedding ceremony of Mr. Robert Erwin and Miss Mary Clarke. The floral decorations were numerous and most attractive. There was a beautiful floral arch in front of the chancel, under which the happy couple stood during the ceremony.

Mr. Charles Clarke and Miss Gertrude Clarke, brother and sister of the bride, and Mr. Charles Kellner and Miss Lauve were the attendants, while Mr. Charles Artz and Dr. H. W. Lubben were the ushers.

After the ceremony at the church the bridal party and numerous friends repaired to the residence of the bride’s parents, corner of Strand and Tenth street, where a reception was held.

The bride is the daughter of Mr. Charles Clarke, the well known contractor of this city, while the groom is a young business man of great promise, at present engaged in the banking business at Wharton, Tex.

The newly married couple will leave for their future home, Wharton, Tex., this morning, followed by the good wishes of the bride’s host of friends in this city and welcomed there by those of the groom.

— Galveston Daily News, April 28, 1893

Marrying the daughter of a wealthy, prominent Galveston business man certainly had its benefits. It wasn’t long before Ervin and his father-in-law became business partners in a financial firm called “R. T. Ervin & Company.” And the banking business continued, as well. In its “Official Bulletin of New National Banks,” The Banker’s Magazine and Statistical Register for May 1893 lists “First National Bank, Wharton, Tex. R. T. Ervin” with assets totaling “50,000.” For Robert T. Ervin, life was good.

By all indications, the Ervins had it made. According to court papers, “R. T. Ervin and Charles Clarke, Sr., were partners engaged in running a private bank at Wharton, Texas. R. T. Ervin managed the business and acted as cashier.” He also continued his side hustle, purchasing his first real estate in Wharton County in November 1893, with more than 30 transactions recorded between 1893 and January 1899.

He also partnered with his father, G. W. Ervin, on holdings in Barry County, Missouri, as reported under the headline, “THEY HAVE STRUCK OIL,” in the December 19, 1895, Cassville Republican:

When Col. G. W. Ervin of Exeter came to this county from Texas, his attention was attracted to the flattering prospect and, enlisting the interest of his son, R. T. Ervin, of Galveston, Tex., began leasing land in Washburn and Sugar Creek Townships. They have 1,500 acres now under lease and [are] taking more as fast as they can get it.

[. . .]

The extent of the oil field is, of course, yet unknown, but Messrs. Ervin & Son are confident that they have a rich thing and will proceed to put down other wells on the land leased. They believe that the field extends to the south into Arkansas and, as soon as practicable, they contemplate erecting a refinery to enable them to put the oil on the market ready for use.

Naturally, considerable excitement was created Friday when the discovery was made known and everybody congratulates the Colonel upon the success of his prospecting. The oil is of a heavy body and is said to be of excellent quality.

Ervin and his wife began having children: Robert Clarke Ervin in 1894; Mary Alice in 1896, possibly named after Ervin’s sister, Georgia Alice, both of whom went by “Alice”; and Evelyn Constance in 1898. The Galveston papers report various and growing investments throughout the mid-1890s. The April 7, 1897 Galveston Daily News reported on Ervin’s continuing good fortune: “Wharton, Tex., April 5.—Mr. R. T. Ervin of the banking firm of R. T. Ervin & Co. of this town has purchased the five corner lots of Mrs. M. E. Anderson on the corner of Rust and West Milam streets and will immediately begin the erection of five brick business houses, one of them to be used as a bank building. The bank will be a two-story structure.”

But things may not have been entirely rosy. Throughout the 1890s, a sometimes bitter dispute arose between cotton farmers regarding the method in which their crops were baled; the camps were divided into “the round bale people” and the “square bale people,” with each side accusing the other of “trying to secure control of the cotton fields” (Halletsville Herald, June 23, 1898). Robert T. Ervin may have been caught in the middle at some point. In a circa September 1932 letter to H. P. Lovecraft, Ervin’s nephew, Robert E. Howard, recalls a tale he must have heard from his mother:

When the uncle for whom I was named—a prominent banker on the coast—was mixed up in the “round bale war,” he hired a private detective to guard his house and protect his family when he himself had to be absent, but he asked no man to protect him. He wore his protection slung on his own right hip. Anyway, when one of his associates was shot down on the streets, the gang that did it ran the sheriff clean out of town. Even when my uncle learned of a plot to murder him as he got aboard the Galveston train, he didn’t ask for a police escort. He didn’t even ask his friends to help him, but they were there in force, and the would-be killers backed down. I’m not telling this to show how brave my uncle was; I don’t claim he was braver than anybody else. As far as that goes, he wasn’t afraid of anything between the devil and the moon. But it just shows that in those days men considered protecting themselves their own personal job, unless the odds against them were too overwhelming.

I have been unable to find documentary evidence for any of this. There is, however, one final drama to relate. The scandal played itself out in the small town newspapers of neighboring communities: Halletsville, La Grange, and El Campo. I have not found mention of it in the Velasco, Houston, or Galveston papers.

A shorter write-up appeared the same day in the Halletsville Herald: “Banker Ervin of Wharton has been arrested and jailed on the charge of improper conduct with his typewriter, a mere child. The girl’s father accepted a check for $5000 in settlement of the affair, but Ervin stopped payment of the check at a Houston bank and his arrest followed.”

The incident was still on people’s minds on March 23, when the La Grange Journal printed this note from the Halletsville Herald: “The Wharton man who accepted a check for $5,000 in payment of his daughter’s honor and virtue should be tarred and feathered and ordered to leave the state. Texas is no place for such people.”

At this late date, it is impossible to know what effect this scandal had on Ervin’s life, both public and private, though we can certainly hazard a guess. In 1899, was this sort of affair enough to ruin a man of Robert Ervin’s standing? What were the social consequences, not only for Robert, but also for his wife and children? Would there be damage to Charles Clarke’s reputation? After what must have been a terrible month of gossip and sideways glances, arguments and tears, Robert Thomas Ervin succumbed to the pressure and died. He was 32.

ERWIN—Wharton, Texas, March 28.—The sad news of the death of Banker R. T. Erwin reached here this morning and caused great sorrow to his many friends here. Mr. Erwin will be greatly missed in the business circles of Wharton, where he was known as a public spirited liberal man, wide-awake to the public interest and a warm friend to the public good. Mr. Erwin’s death took place in Galveston, where he went for medical attention.

—Houston Daily Post, March 29, 1899

The smaller papers were less kind: “R. T. Ervin, the Wharton banker who recently figured in a scandal case, died at Galveston a few days ago” (Halletsville Herald, April 6, 1899).

In Afloat on a Full Sea: the Clarke Family of Galveston Island (2014), Robert Ervin’s great-granddaughter, Evelyn Joann Russell, condenses all of the above into a few paragraphs; her focus is on the Clarke family, not Robert Ervin. While she does not mention the scandal, she does provide some interesting details of Ervin’s final moments: “Mary had lost her husband Robert to some sudden affliction that no one understood yet. What could cause an intelligent young businessman to start raving and screaming and go on like that for three days? They had taken him from his home in Wharton to the hospital in Galveston but no one there knew what to make of his illness. Finally, the poor man’s heart or brain or something vital to his existence just stopped and the father of three little children was pronounced dead.”

According to the death certificate and mortuary records obtained from the Rosenberg Library’s History Center in Galveston, R. T. Ervin died on March 27, 1899, at 2:00 a.m. at the John Sealy Hospital on the corner of 9th and Strand, a block away from the Clarke residence. The immediate cause of death is “cerebral effusion,” with a “remote cause of death” listed as “acute mania.” The scandal had indeed taken its toll.

Details of the funeral and its aftermath appear in Afloat on a Full Sea:

The minimal final services were held before a distraught family on March 28, 1899, the day after his death, at Grace Episcopal Church in Galveston. Burial took place in the Clarke’s large plot at Cahill’s Cemetery (since renamed Evergreen Cemetery) on Broadway. The widow was only twenty-nine years old. She had the immediate and sole responsibility of caring for her three small children. Her grief rendered her completely unable to cope with the ordinary daily tasks of life. Not knowing what else to do, she arranged to have all of her household goods and personal items moved from Wharton to her parents’ home on Strand.

Russell later says that Mary “led a reclusive life in the large house and turned over primary care of the children to the same servants who had raised her.” There are four servants living in the household during the 1900 Census. Russell also adds that Mary “would remain dependent on others for the rest of her life.”

Epilogue—

On March 31, 1899, G. G. Kelley, attorney-at-law, appeared before the honorable G. S. Gordon, judge of the county court at Wharton. He informed the judge of Ervin’s passing, the fact that he left behind a wife and three children, and that “he left considerable community property of himself and petitioner [Mary Ervin] the principal portion of which lies in Wharton County, Texas.” Kelly asked for an appraisal of the estate and that after the inventory, the judge “vest in [Mary Ervin] the rights and powers of survivor in community as provided by the statutes of this state.” It was all done by April 5, 1899, when Mary Ervin was “authorized and empowered to control, manage, and dispose of such community property” listed in the inventory. When it was all said and done, Mary was sitting on top of $28,911.00—that’s a cool million in 2023 dollars.

Not that she needed it: as we have seen, the Clarkes were very well off. In fact, they built what I’m tempted to call a mansion on Avenue I in Galveston shortly after Ervin’s death. In her book, Russell says that the Clarke family, including the bereaved Ervins, moved into the newly constructed home just before the famous hurricane hit Galveston early in September 1900: “It proved to be a formidable shelter for the family and strangers who assembled there to ride out the raging winds and torrents of rain. Among them were relatives of the late husband of Clarke’s daughter Mary Clarke Ervin. They had traveled from North Texas to see the Clarke residence and to enjoy a few days on the beach. After the storm, they found themselves stranded by a historic disaster.”

Who were these relatives? They are unnamed in the text, but also just before the hurricane, Robert Ervin’s sister, Hester Jane Ervin, was on the move. She had spent much of the 1890s traveling between her father’s home in Exeter, Missouri, and her siblings’ homes in Indian Territory and Texas. The June 30, 1899 Abilene Reporter ran this item: “Miss Ervin, of Missouri, who has been visiting in Galveston and Dallas, was due to arrive here this afternoon to visit her sister, Mrs. Cobb, at the California house.” It seems likely that Hester had gone to Galveston to pay her respects. Might she have returned in September?

How close Hester Ervin-Howard remained to her brother’s family is a mystery, but there is only one mention of the Galveston Ervins in Robert E. Howard’s correspondence, and it is not in relation to one of his visits there: “Relatives of mine were in Galveston when it was washed away in 1900, but fortunately all were saved, though many of their friends were drowned” (Letter to H. P. Lovecraft, ca. August 1931). Perhaps this quote is the source of Russell’s information and she was unaware that Howard was probably referring to Mary Ervin and her children, who were, after all, his relatives.

Mary Ervin never remarried. She died at the end of 1946, on New Year’s Eve.

Special thanks to Damon Sasser for getting the ball rolling on this back in March of 2014; to my parents, for going to Galveston in May 2017 and visiting the cemetery for me; and to Will Oliver, for visiting the courthouses and communities that I haven’t been to . . . yet.