[by Rob Roehm. Originally published May 1, 2011, at rehtwogunraconteur.com; this version lightly edited.]

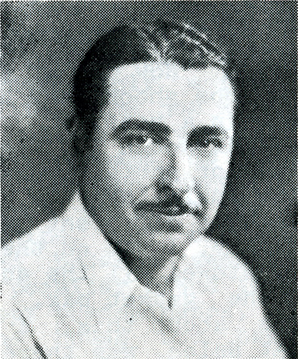

Born in Chicago on July 1, 1891, and author of at least thirteen novels (most appearing as serials in the pulps), not to mention all the short stories, articles, letters, and even poems, Otis Adelbert Kline is perhaps best-known to readers of the Two-Gun blog as the author of The Swordsmen of Mars, and as the one-time agent for Robert E. Howard. In the 1920s, Kline hobnobbed with Farnsworth Wright and E. Hoffmann Price at his Chicago home. A successful pulp writer himself, Kline started agenting for others in 1932 or 1933. At the suggestion of Price, himself a client of Kline’s, Robert E. Howard joined the stable of authors that Kline served.

The earliest Kline-Howard connection that I’m aware of is Kline’s May 11, 1933 letter to Howard. In that missive, Kline mentions having at least four Howard stories already on hand: “The Yellow Cobra,” “The Turkish Menace,” “The Jade Monkey,” and “Cultured Cauliflowers.” Not only did Kline attempt to place Howard’s fiction in different markets, he offered tips and strategies to more effectively produce those stories.

According to the Kline Agency ledger, “Wild Water” was received on June 15, 1933. The very next day Kline returned it, saying that while it was loaded with “excellent local color, powerful characterizations and fast action,” he was afraid he couldn’t sell it “because the plot is not powerful enough to support a story of this length.” While I don’t agree with Kline’s assessment, he apparently knew what he was talking about at the time. Howard rewrote the story and sent it back that October. It was shopped around by V. I. Cooper, who sent it to Fiction House, Wild West Stories, and others, to no effect. The story remained unpublished long after Howard’s death.

And so it went; Kline continued to place, or not place, Howard’s work. In 1935, business must have been going well, as Kline enlisted the aid of Otto O. Binder. Binder went to New York late in 1935 to be closer to the publishing scene than Kline’s Chicago offices allowed. And he had some success, placing several of Howard’s “Spicy” stories with Trojan Publications, as well as other items, like “Black Wind Blowing” and “The Curly Wolf of Saw-Tooth.” After a rough start in New York, when things started picking up, Binder wrote the following to his brother Earl on June 7, 1936:

The business is beginning to pick up a bit at that, though. I wish all our authors were like Robert E. Howard. Since I’ve been here, I’ve sold $700 worth of his stuff, getting him into Argosy, and into Star Western, and Complete Stories S&S. He’s thirty years old and has sold 22 different magazines and over 125 stories altogether. I’ve seen his picture—he’s a rough and ready Texan and claims he wears no underwear because there’s no sense to it!

Howard’s suicide a few days later certainly negated that “wish.” Binder sent a postcard to Richard Frank, a friend in Pennsylvania, mentioning the suicide. Rich responded in a July 9, 1936 letter:

Give me more dope on the suicide of ROBERT E. HOWARD. Funny thing about my hearing of the tragedy. Your card arrived telling me of the suicide and while I was waiting at the post office I saw a magazine thrust into my box. I pulled it out and it was the July issue of WEIRD TALES with Howard’s latest story, “Red Nails,” featured on the cover. It gave me a peculiar feeling to hear of an author’s death and then, in the same mail, receive his latest tale.

And while there would be no new Howard items to show, Kline Associates got first crack at the fabled trunk, and Kline continued to represent Howard through his father, Doctor I. M. Howard. During this time, A Gent from Bear Creek was published, and the foundations for Skull-Face and Others were laid. This stormy relationship would last until the doctor’s death in November 1944, but that was not the end of Otis Kline Associates’ relationship with the works of Robert E. Howard.

In his will, Doctor Howard left “all property, both real and personal” to his friend Doctor P. M. Kuykendall. This included the literary rights to Robert’s work. And, while the actual items—typescripts, clippings, letters, etc.—were shipped off to E. Hoffmann Price in California, Dr. Kuykendall received royalty checks from Kline. Business was slow.

Kline died in October 1946, but his agenting business lived on. His daughter, Ora Rossini (later Rozar), took over the practice for a year and a half, but when her husband was transferred to Texas, of all places, she “turned over everything to Oscar Friend, including material published and unpublished, records, files, etc.” Oscar Jerome Friend was a veteran writer himself, as well as editor of Thrilling Wonder Stories from 1941 to 1944. Upon purchasing Kline’s business, he set out to fatten it by contacting various authors, including Binder and British science fiction writer Eric Frank Russell, and asking them to let him represent them. The Howard items were probably not very high on his priority list. Things change.

In 1950, a small specialty publisher purchased the rights for Howard’s The Hour of the Dragon—Gnome Press. Conan the Conqueror, as the novel was re-titled, was the first in a series of books covering the Cimmerian’s exploits. From all accounts the series wasn’t exactly lucrative, but it did show some possibilities. Enter L. Sprague de Camp.

According to de Camp’s introduction to Gnome’s King Conan (1953), he had been acquainted with Oscar Friend and, when he learned from Donald Wollheim that Friend had “a whole pile of unpublished Howard manuscripts,” he rushed right over. This was November 30, 1951. Upon his arrival, he met Harold Preece, and then Friend “hauled out the carton of manuscripts—about twenty pounds of them.” Among the stash, three Conan tales were discovered, and “it was agreed that [de Camp] should rewrite these stories—not, however, to turn them into typical de Camp pieces, but to create as nearly as possible what Howard would have produced if in his later years he had undertaken to rewrite them himself with all the care he could manage.”

Meanwhile, Doctor Kuykendall had decided that he’d had enough of the literature business and made Friend an offer: “We would consider a sale price of three thousand dollars for all rights, and a complete release of any claim to future royalties that might accrue.” Friend responded on March 14, 1954, saying that the property wasn’t really worth that much, and offered $1,250, instead. The reasons for this reduction in price seem quite reasonable, for the time. There was, after all, no guarantee that the Conan name would take off.

Friend described his efforts to continue the Conan series, and the amount of work that would entail:

Now let us consider the future prospect of a continuation. In the first place, I have to guide, cajole, help plot, supervise, etc., the future books, and keep a firm rein and control—or the project would go completely haywire and finally bog down in complete ruin. There is one rather smart writer now who has been doing some work for us in rewriting several Howard stories, and he keeps pressing for a larger cut and keeps slipping in side remarks to the effect that if he wants to he can and will go ahead on his own and write about Conan as the author is dead, etc., etc. And I’ve warned him that I’ll sue the pants off him if he makes one silly move of this nature before the CONAN material runs out of copyright (56 years).

We all know how that worked out.

Sometime later, Kline’s daughter recalled that “Oscar moved to another place and I suspect disposed of practically all OAK material, records, and files.” This may be when the Howard items listed on the Kline lists disappeared. Items like “The Phantom Tarantula” and “Footprints of Fear,” which are listed on the list, but no copies have ever turned up.

Friend enlisted the aid of his wife, Irene M. Ozment, as vice president, and his daughter, Kitty F. West, as early as 1955, with West acting as secretary for Kline Associates and sending letters to the above-mentioned Eric Frank Russell. Around this time, also, a young Howard fan named Glenn Lord secured the rights to Howard’s poems and published Always Comes Evening (1957) with Arkham House. Friend’s health began to fail in the early 1960s, and he died on January 19, 1963. His wife and daughter continued the agency through 1964. In the interim, Dr. Kuykendall had also died, leaving the rights to Robert Howard’s works to his wife and daughter. With the Kline agency closing up shop, the heirs were in need of a new agent.

In Costigan #7 (REHupa mailing #9, May 1974), Glenn Lord explains what happened next: “The Howard heirs asked Mrs. West to find another agent to handle the Howard material, and L. Sprague de Camp was asked, but turned it down due to his own writing. De Camp suggested that I might be a good possibility.”

The Kuykendalls apparently agreed and, in the winter 1965 issue of The Howard Collector, Lord made the announcement: “Otis Kline Associates, the agent for the Howard Estate, went out of business at the end of 1964. I have accepted the handling of the Howard material for the Estate.”

The rest, as they say, is history.

[Note: Most of the information used to write the above came from the forthcoming collection from the Robert E. Howard Foundation Press, The Collected Letters of Doctor Isaac M. Howard. Ora Rozar’s information is from OAK Leaves #2, Winter 1970-71, edited by David Anthony Kraft. The letters to and from Otto Binder are unpublished; copies were provided by the Cushing Memorial Library at Texas A&M. Binder’s list of sales appeared in OAK Leaves #5, Fall 1971. Letters from Kline Associates to Erick Frank Russell are unpublished; they are housed at the University of Liverpool Special Collections and Archives.]